Scripps Coastal Reserve Biodiversity Trail

1: Welcome!

Welcome

The Scripps Coastal Reserve is one of four ecological reserves managed by the University of California San Diego. The others are Kendall-Frost Marsh Reserve, Dawson Los Monos Canyon Reserve, and Elliott Chaparral Reserve. These reserves are part of the larger UC Natural Reserve System, a network of 41 wild lands that are set aside to fulfill the mission of the University of California: education, research, and public service.

If you are reading the “Welcome!” sign at the reserve, you are about to walk a 0.5 mile trail and experience what this entire coastal region might have looked like a little over 100 years ago. Take a deep breath. You may be able to smell the coastal sage (Artemisia californica) that is the namesake plant of the coastal sage scrub vegetation community on the mesa top. Gently touch a few leaves on the shrubs as you walk along the path. You will find that some are soft and delicate, while others are thick with a waxy coating. These different characteristics represent very different ways of adapting to the hot dry summers that we experience here in southern California. You can read all about that on the next trail sign, “Photosynthetic Friends”.

A few things at the Scripps Coastal Reserve are different than they were 100 years ago. Of course the buildings you see surrounding the reserve were not here. But there are plants that would not have been here either. You can learn about plants that have taken advantage of the last 100 years of human disturbance on the “Photosynthetic Foes” sign.

Continue on the trail to learn about some of the animals that live here, the current human impacts, the history of the reserve, and the Kumeyaay people that have lived here since time immemorial.

2: Native Plants: Photosynthetic Friends

Mediterranean Climate

Here in coastal California, and thus at the Scripps Coastal Reserve, we live in a Mediterranean climate.

Hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters are characteristic of this climate. Other locations with a Mediterranean climate include southern and southwestern Australia, Chile, the Western Cape of South Africa and throughout the Mediterranean Basin. The plant communities present in this climate have evolved traits that allow them to thrive, even in the hot and dry conditions we experience here in San Diego in summer and fall.

Plant Communities

The two most common plant communities at the Scripps Coastal Reserve are chaparral and coastal sage scrub. Plants in these different communities have different ways of limiting water loss in our hot, dry summers.

Chaparral

Many plant species in the chaparral have sclerophyllous leaves. These are thick, waxy, long-lived leaves that help to limit the evapotranspiration of water and prevent wilting during very dry conditions. Limited water loss also means limited carbon dioxide gain, so these plants also have a relatively slow rate of photosynthesis. This is a typical type of trade-off that occurs in the natural world. Plants can not have their cake and eat it too, any more than we can!

These chaparral plants are mostly evergreen shrubs and smaller trees; chaparral has been called “the elfin forest.” Chaparral is hard to walk through because the plants are packed in densely (suggesting more resources, namely water, than in coastal sage scrub). Some examples of chaparral plants include: Lemonade Berry (Rhus integrifolia), Coyote Brush (Baccharis pilularis), and California Buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum). If you are at the Scripps Coastal Reserve, the north-facing slope of Black’s Canyon is covered in chaparral.

Coastal Sage Scrub

Plants in the coastal sage scrub have different traits to cope with our hot, dry summers. Many of the species in this plant community are drought deciduous. These plants lose their leaves during the harshest time of year – our hot and dry summer and fall – and regrow new leaves when the rains start again in the winter. These plants have high rates of photosynthesis when they are growing in the spring, but then totally shut down when it gets too dry. If you are at the Scripps Coastal Reserve in the fall, it may seem like many plants are dead but they are not – they are just waiting for favorable conditions. Some examples of coastal sage scrub plants include California sagebrush (Artemisia californica), coast brittle-bush (Encelia californica), and rattlesnake weed (Astragalus trichopodis).

Who are our photosynthetic friends?

Native plant species play a critical role in ensuring the preservation of our ecosystems. They are adapted to our climate conditions and are able to survive extreme dry periods without all the irrigation our horticultural plants need. Native plants don’t need to be mown or fertilized or sprayed with insecticide, yet they capture and store carbon and are thus key allies in our fight against climate disaster. Native plants provide resources for other organisms: many of our native pollinators, animals such as bees and butterflies, are specialists on native plants and would not survive without them. Birds, such as the endangered California gnatcatcher will only nest in native vegetation.

Think about including native plants in your neighborhood or garden, they are beautiful and resilient and provide food and homes for a diverse array of native animal species.

Lemonadeberry (Rhus integrifolia)

Lemonadeberry (right), is a shrub native to the coast of Southern California. Besides the commonplace light pink berries, lemonadeberry is also known for its waxy leaves and small fragrant flowers that begin to bloom from late winter into spring. This species is considered evergreen: most of its leaves remain present (and green) all throughout the year.

Coyote Brush (Baccharis pilularis)

Coyote brush (left), or broom, is a shrub common to the chaparral plant community and is known for its characteristic 'fluffy' white seeds that cover the plant in the fall season. Similar to a dandelion, these seeds are dispersed by the wind.

The species is also unusual in that it is dioecious: some individual plants have only female flowers and other individual plants have only male flowers.

California Buckwheat (Eriogonum fasciculatum)

California buckwheat (right) is a common shrub found in both chaparral and coastal sage scrub. The plant ranges from the coast of southwestern California east into the Mojave Desert. Identification of California buckwheat is easy for most of the year - from late summer to early winter their seeds are abundant and are an unmistakable deep rusty red. Whole hillsides can look red due to California buckwheat.

The California buckwheat plays a critical role in the production of honey across the state as it is one of the few native plants capable of producing nectar that pollinators can harvest throughout dry months.

California Sagebrush (Artemsia californica)

The California sagebrush (left) is the namesake plant for the coastal sage scrub plant community and is characterized by its smell. In general, animals seem to dislike the scent emitted from these plants which reduces herbivory. In contrast, humans tend to enjoy the smell of the sagebrush. Due to its fragrance, the plant is also referred to as “Cowboy Cologne” because of its beneficial properties to those seeking to smell better. In the past, this plant was also used for medicinal purposes by the Kumeyaay people.

3: Invasive Plants: Photosynthetic Foes

Non-Native Species

Non-native plants are species that are not indigenous to that area. In California non-native species are those that were not here before Europeans arrived. Invasive species are a subset of non-natives that have a negative impact, for example they can reduce biodiversity by outcompeting native plants for resources (ie. water, nutrients, space.). The replacement of native plants with outcompeting non-natives often creates a monoculture and can make the area far more susceptible to external stressors such as fire, and can harm the native animals that depend on native plants for survival.

Invasive plants often thrive on human disturbance - whether that is physical disturbance (such as digging or plowing) or disturbing the nutrient or water cycles (fertilizer or irrigation runoff, for example). The Scripps Coastal Reserve has had a history of human disturbance (see History, Human Impacts) and indeed is plagued by invasive species, most of which come from Mediterranean climate regions. We have an active volunteer program to remove invasive plants (see Get Involved) to ensure continued diversity of both plants and animals at the reserve.

Photosynthetic Foes

Crystalline Iceplant (Mesembryanthemum crystallinum)

The crystalline iceplant (left) is native to South Africa, a place with a Mediterranean climate similar to ours. Like all plants that live in this climate it has to cope with hot, dry summers. Crystalline iceplant has a special trick for this. Plants need both carbon dioxide and sunlight to photosynthesize. Most plants open their stomata during the day to collect CO2 when it's sunny. But they lose a lot of water by doing this. Crystalline iceplant collects CO2 at night instead and keeps its stomata closed during the day. It really conserves water this way. But how does it photosynthesize without sunlight? It doesn’t, it stores the CO2 as malic acid at night, then converts it back to CO2 during the day. In this way it has both CO2 and sunlight at the same time, without losing water! This plant's ability to use this CAM photosynthesis makes it an extreme competitor against native species and plays a critical role in explaining the incredible range of this invasive plant within dry environments.

Devil’s Thorn (Rumex spinosa)

Devil's thorn (right) is native to the Mediterranean, a location with a climate similar to the southern California coast. Devil's thorn receives its name due to its spiny seed pods that tend to stick to animals or people. The plant is common near areas of disturbance, such as hiking trails, due to the seed's great success at attaching to the bottom of one's shoe. Since this is a relatively new invader to the Scripps Coastal Reserve we are really trying to get rid of it before it becomes more widely established

Maltese Star-Thistle (Cemtairea melitensis)

Maltese Star-Thistle (left), or Tocalote, is a plant native to the Mediterranean climate regions of Europe and Africa. This plant is an annual, meaning it is able to complete its entire life cycle within a single growth season. While not as invasive as its more common relative, the yellow starthistle, if left unchecked the Maltese star-thistle can thoroughly outcompete native species for resources and space.

Want to learn more?

4: Animals: Meet the Neighbors!

Finding Animals

So you’re outdoors and hoping to spot some animals? Here are some tips on maximizing your chances:

Tip #1: Stay as quiet as possible

Animals are easily scared. Many animals have more acute hearing than humans, it won’t take much noise to startle them. Slowly walk on your heels, or don't move at all if possible!

Tip #2: Know what you’re looking for

Whether it’s a lizard, a bird, or something larger you’ll want to know whether to keep your eyes on the ground, the sky, or atop a rock. You will also want to know when those animals are out and about. For example, it’s much easier to find ectotherms (cold-blood animals like a lizard or snake) on warmer days when it is warm enough for them to be active. Many animals in coastal sage scrub habitats are crepuscular - most active at dawn or dusk.

Tip #3: Look for signs

Footprints, scat, or any other unusual signs can clue you in to exactly what may be hiding around the area. Finding fresh scat could be a key indicator in letting you know just how long ago they came through the area!

If you do find an animal in their natural habitat, give them more than enough space to move freely. If they’ve noticed you, you are likely too close!

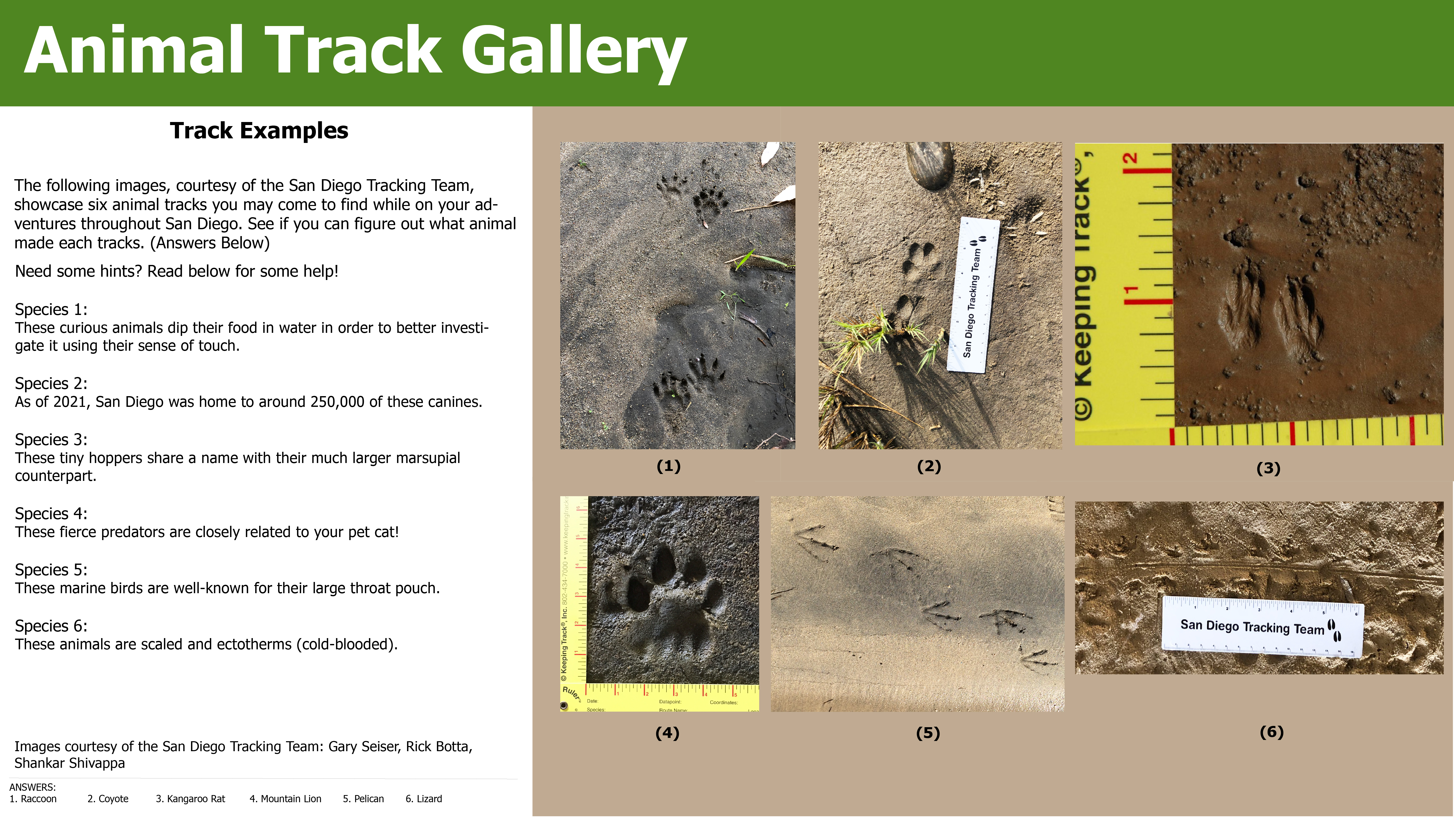

If you want to learn how to track animals in the wild you can take a course with the San Diego Tracking Team

Track Gallery

Animal Conservation

Animals are a huge reason why the preservation of natural areas is so important. The more we develop, the less habitat there is available for animals to exist! While we may have clear home boundaries located within four walls, the homes of animals can be vast: such as the blue whale which may travel throughout all the major oceans during its lifetime.

Having a large variety of animals in any ecosystem is critical for its long-term survival. High biodiversity has many benefits to us as well. For example our world’s economy is extremely reliant on biological resources, like pollinators that are essential for global agriculture to be successful!

5: Bees: What’s the Buzz?

The Honey Bee

Throughout California, the reserve included, the most common bee species present is the western honey bee (Apis mellifera) pictured on the right. These bees are not from here, they were intentionally introduced with the early Europeans that came to the New World. You can recognize western honey bees by their size (they are big, smaller only than bumble bees), common, slow, and methodical. On any flowering bush they will visit flower by flower. Because they are so slow and preoccupied with their job of collecting pollen and nectar, they make great subjects for colorful photography.

Western honey bees are social, they live in colonies with a queen and many daughters that raise the young, forage for pollen and nectar, and defend the hive. They process the nectar they collect with enzymes and evaporation to prevent spoilage, and store it in honeycombs for later use. This is what we call honey. Honey bees are best thought of as a domesticated species. Farmers manage colonies by providing shelter and occasionally food and they harvest the honey in return. But in San Diego there are also many, many feral colonies - colonies that escaped and now live on their own in any sheltered space - holes in trees, utility boxes, the crawl space underneath structures, etc.

Native Bees

Western honey bees are not the only bee at the reserve, however. San Diego County has over 600 species of native bee.

Native bees come in an array of different shapes, sizes, and behaviors. From green to yellow, to fuzzy or bald, and tiny to huge, they all feed on nectar and pollen but often in different ways. For example, the long-tongued bee (Anthophora centriformis), pictured on the left, prefers deep flowers that require a longer tongue to reach the nectar. Most bees carry pollen in basket-like things on their legs but bees in the family Megachilidae, as pictured on the bottom left, carry pollen using a pollen brush on the underside of their abdomen. And bees in the genus Hylaeus, as pictured on the right, don’t have any body structures to carry pollen - they swallow it and later regurgitate it into their nest.

The behavior of native bees is different as well - while western honey bees are slow and methodical, native bees are often fast and very skittish, zooming from plant to plant in a seemingly chaotic pattern. Native bees are also mostly solitary (bumblebees are an exception). While western honey bees live in bee hives with many sisters, native bees prefer living underground in simple holes, deep, intricate mines, hollow twigs or stems, or other structures. At the reserve, look for small holes in the ground. They are almost certainly homes to insects, likely native bees!

The magic of having native bees comes in their efficiency for  pollination. While honey bees pollinate common flowers, they often don’t recruit to native species that are infrequent in the habitat. They also don’t have specialized morphologies or behaviors to pollinate certain plants. For example tomatoes & eggplants require bees to vibrate at the right frequency before the pollen is released; only bumblebees do this behavior. Many native bees specialize on certain plant species, both the plant and the bee need each other.

pollination. While honey bees pollinate common flowers, they often don’t recruit to native species that are infrequent in the habitat. They also don’t have specialized morphologies or behaviors to pollinate certain plants. For example tomatoes & eggplants require bees to vibrate at the right frequency before the pollen is released; only bumblebees do this behavior. Many native bees specialize on certain plant species, both the plant and the bee need each other.

Western honey bees are important in agriculture, they provide pollination services for many commercial crops. But it is important to remember that western honey bees are not the only bee species, nor are they the most important bee for our native plants. If we want to maintain diverse plant communities, we need a diverse bee community. But protecting honey bees is not bee conservation any more than protecting chickens is native bird conservation.

Want to learn more?

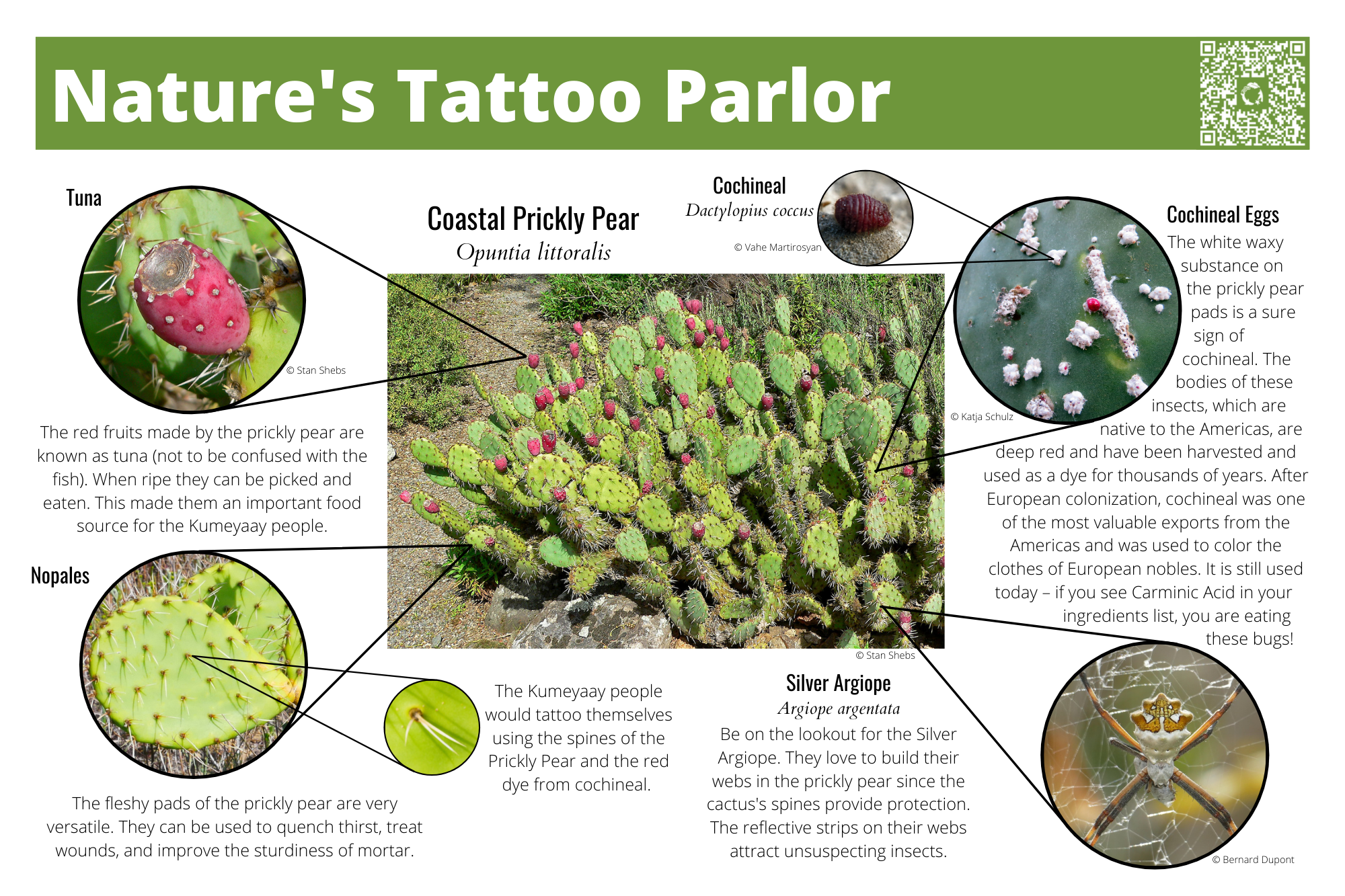

6: Coastal Prickly Pear: Nature’s Tattoo Parlor

The Prickly Pear Cactus

To the Kumeyaay people, every component of the coastal prickly pear cactus had a use. The bright red ‘tuna’ was used as a food source, the pads or ‘nopales’ could also be used for food or even as a water source, and the needles atop the pads were used in tattooing. Even still today, the nopales and tuna fruit are used as ingredients for many cultural dishes.

Ensalada de Nopales (Cactus Salad)

Ingredients:

- Nopalitos (Pre-Sliced Nopales) or Nopales (Cactus Pads)

- Salt/Pepper

- 2 Roma Tomatoes

- 1/4 Onion

- Cilantro

- Cotija Cheese

- Lime

- Olive Oil

Steps:

- Bring a pot of water to boil, ensure the water is properly salted.

- If necessary, carefully remove the thorns from your nopales and dice into cubes.

- Add the diced nopales into the water to boil for 15-20 minutes, or until tender.

- Dice your tomatoes, onion and cilantro.

- After the nopales are tender, remove them from the pot and rinse them thoroughly in cold water.

- In a salad bowl, mix the rinsed nopales with the diced tomato, onion, cilantro, and dash of olive oil.

- Add salt, pepper and lime for taste.

- Top with crumbled cotija cheese.

- Enjoy!

Meet The Chef

Abuela Amparo was born November 26th, 1948 in the Districo Federal (now known as Mexico City). When making this recipe in Mexico it was much more common to use intact nopales (thorns and all), so sitting down and dethorning the pads was usually part of her process. Even now where it is just as easy to find pre-diced and de-thorned nopalitos in the local mercado, Abuela Amparo still prefers to buy the entire pad and prepare it herself. She recommends eating the ensalada in a warm corn tortilla, or as a side to grilled carne asada.

We hope you can enjoy this treat but the plants at our reserve (and other reserves and public parks) are protected. Please don’t pick prickly pear pads or fruits from our plants. Like Abuela Amparo you can buy them from a store or from a farmer that grows these plants for sale.

7: Insects: Sorry to Bug You

Bugs Matter

Bugs are seriously underappreciated animals . (Although the term “bug” technically refers to one suborder of insects, it is colloquially used for all insects and spiders). If it weren’t for insects the crops we grow would have few pollinators, our global food webs would collapse, and we would be knee-deep in waste due to inefficient decomposition. Despite their benefits to society, a 2019 analysis has found that 40% of insect populations worldwide are declining and that a third of those populations are endangered. Regardless of their small stature, it is undeniable that insects play a large role in our planet’s well-being.

Insect Interactions

At the Scripps Coastal Reserve, you have the perfect opportunity to witness insects in their natural habitat doing what they do. If you watch insects work, it becomes clear that their lives are far more complex and interesting than one would imagine. The Argentine ant is one species that is hard to miss at the Reserve. These ants farm other insects, just like humans farm cattle or chickens. Aphids and their relatives produce a substance called honeydew, the excess sugar and water from the diet of plant phloem. Honeydew is a favorite food of Argentine ants and they go to great lengths to ensure they have a plentiful supply. The ants will protect the aphids, fighting off parasitoids and predators just like a farmer will build a coop to protect chickens from coyotes. You can find honeydew-producing insects by locating a black mold-like substance on a plant’s leaves. This is called sooty mold, a mold that grows on the residue of uneaten honeydew. In southern California, where there is honeydew there are almost certainly Argentine ant farmers.

Another insect a close observer is sure to see is the colorful Harlequin bug, as pictured on the left, These insects feed almost exclusively on the plant Peritoma arborea or bladderpod and suck sap from the plant, typically leading to its wilting, browning and eventual death. Incredibly, a harlequin bug can spend its entire lifetime on a single plant.

An insect you probably won’t see, but can see the evidence of is the Baccharis stem gall moth (Gnorimoscema baccharisella). This insect creates a gall on its host plant, coyote broom (Baccharis pilularis). A plant gall, as pictured on the right, is a swelling of a plant’s leaves or stems that happens when an insect lays her eggs inside the plant tissue. Coyote broom is attacked by several different species of gall makers, including one fungus, but the stem gall might be the easiest to see. The galls look like round swellings of the stem. Why the plant reacts to the insect by swelling and forming a gall aren’t entirely understood, but the insect benefits from the protection and nutrients that the plant gall provides . Look for fallen galls near the base of a coyote broom plant, they will have characteristic holes the insects have eaten to escape the gall when the moths have grown into adults.

8: Birds: Feathered Friends

Common Birds

Seasonal sparrows, colorful hummingbirds, and impressive peregrine falcons all call the Scripps Coastal Reserve home. Take a look at the most common birds sightings at the reserve found by our local birders here. Feel free to make your own observations and contribute to the page in order to aid in the conservation efforts for our local birds.

Bird Identification

Need some help telling your crow from a raven? Or maybe you just need a refresher on how to identify local birds? Read below for some tips to help with your bird identification.

Tip #1: Think about your location/season - what birds should be there?

While some species of birds can be seen almost anywhere (crows, for example), other birds are very picky about their habitat. California gnatcatchers, for example, only live in coastal sage scrub habitats, like the Scripps Coastal Reserve. Similarly, many birds migrate during the spring and fall and thus are not in the same place all year. For example, the white-crowned sparrow is a very common winter resident at the Scripps Coastal Reserve but spends the summers in Canada and Alaska. If you think you’ve seen a certain bird, ask yourself whether it would make sense for them to be there at that time. The distributions of most bird species are well documented and are included in all of the field guides, both paper and electronic. Occasionally a bird is seen outside of the range that is usual for that species. This is highly unusual, however, and the birding community goes crazy when it does happen.

Tip #2: Pay as much attention to the bird’s habits as to its appearance

Even without binoculars you can observe a bird’s behavior. Is it hovering in front of flowers, seeming to sip nectar? It’s probably a hummingbird. Is it soaring overhead? It’s probably a hawk. Is it on the ground scratching at the leaf litter, maybe looking for insects? At Scripps Coastal Reserve that could be the California thrasher or a towhee. Most expert birders narrow down the possibilities based on behavior, size, location, and then look closely to identify what species of hummingbird or hawk they are seeing.

Tip #3: Check out bird identification apps on your phone. Here are a few -

- Audubon Birds

- BirdsEye (North America)

- iBird Pro

- eBird

- Merlin

- Seek by iNaturalist

- Sibley eGuide to Birds

The apps include methods for either scanning the bird using your camera, inputting characteristics of your bird, or identifying the birds based on their calls. The Merlin app will even listen to your recording of a bird song or call and make an identification!.

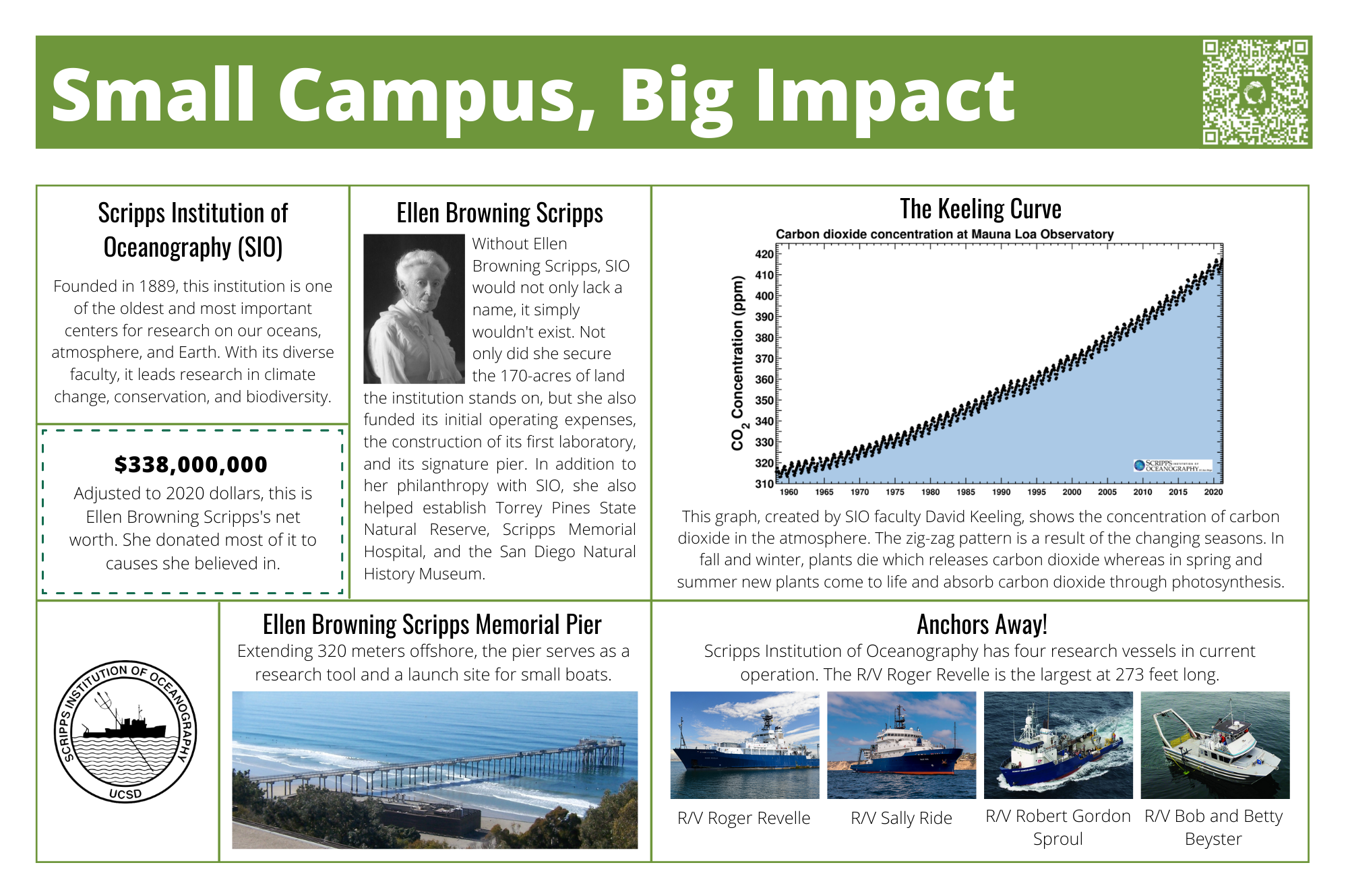

9: Scripps Institution of Oceanography: Small Campus, Big Impact

History

Built adjacent to the Pacific Ocean, the Scripps Institution of Oceanography (SIO) sets the precedent for marine research around the world. Founded in 1903 (then called the San Diego Marine Biological Station) SIO became a key component of the University of California system only a decade later.

While the original founders of the institute included Fred Baker, a San Diego local and mollusk-researcher, and William Emerson Ritter, a professor of Zoology from the University of California, the namesakes for the organization are Edward Willis Scripps and his half-sister Ellen Browning Scripps. The Scripps siblings were philanthropists who used their resources to fund the developing institute—and many other organizations throughout San Diego including Scripps College, the La Jolla Children’s Pool, the Scripps Research Institute and the Torrey Pines State Natural Reserve.

The Scripps Institute of Oceanography had grand connections with the United States military following the first world war. With a newfound understanding that our enemies can come from abroad, the U.S. military hoped to better understand the ocean in order to grant themselves the advantage. As the first institute of its time within the United States, SIO became the center for the University of California’s “Division of War Research”.

Research

Roger Revelle, the director of SIO from 1950 through 1964, is said to have ushered in the beginning of modern climate science through his work at the institute. Research done by Revelle and Hans Seuss, a fellow SIO researcher, would be some of the first to suggest that carbon dioxide released by burning fossil fuels was largely absorbed by the ocean and that an increase in emissions would lead to an increase in the greenhouse effect. Within their paper they wrote, “human beings are now carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment of a kind that could not have happened in the past nor be reproduced in the future.”

“human beings are now carrying out a large-scale geophysical experiment of a kind that could not have happened in the past nor be reproduced in the future.”

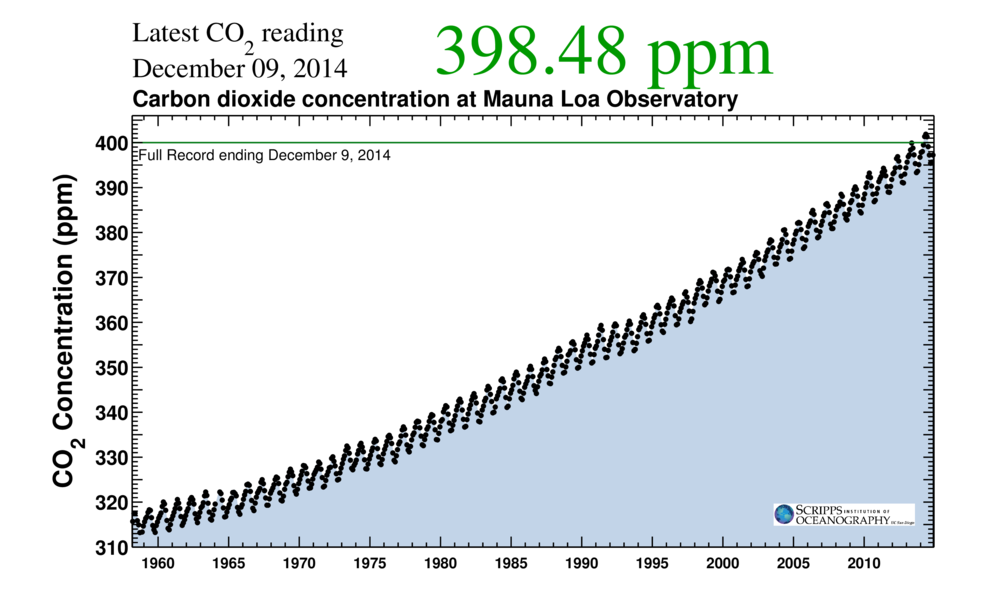

Following the direction of Roger Revelle, Charles David Keeling would also begin work in measuring levels of atmospheric carbon dioxide. His work, now widely known as the ‘Keeling Curve’, would be the first evidence of its kind showcasing the rapidly increasing levels of carbon dioxide within the atmosphere. Understanding the exact rates of increase can aid in the global effort to meaningfully reduce our emissions and prevent further damage to our planet.

Birch Aquarium

If the incredible views at the reserve piqued your curiosity as to what interesting organisms might live in the ocean below, why not pay a visit to the Scripps Institute of Oceanography’s primary method for public outreach— the Birch Aquarium.

Located right above the main SIO campus, the Birch Aquarium is home to more than 60 marine habitats and includes an impressive collection of artifacts and animals including seadragons, penguins, and a sea turtle!

10: Ocean Acidification

Ocean Acidification

As its name suggests, ocean acidification refers to the downward trend of the ocean’s pH. This trend corresponds to the rise in carbon dioxide emissions following the industrial revolution. The ocean is becoming more acidic because excess carbon dioxide combines with water to form carbonic acid. This is a weak acid, but it does what all acids do - it releases hydrogen ions which lowers the pH of seawater. Most living things are very sensitive to pH. A teeny change in the pH of your blood could kill you, for example. Organisms that live in the sea are similarly very sensitive to pH. Combating ocean acidification requires a global effort to reduce carbon dioxide emissions.

Increasing carbon dioxide impacts the ocean in many ways. (Click here for more examples.) Algae, which thrives given excess carbon dioxide, can rapidly bloom causing an increase in the release of toxins that kill sensitive sea organisms. An increasingly acidic ocean can prevent coral reefs from growing pr maintaining their structures. Certain fish have trouble locating predators or prey. One of the most direct impacts of ocean acidification, however, is seen in shell-building species including oysters, clams, and mussels.

Shell-Builders

In general, the shells of sea organisms weaken as oceans become more acidic. In sea water that is more acidic, fewer carbonate ions are available for these organisms to create and fortify their shells. (Those excess hydrogen ions bind with carbonate to form bicarbonate, locking the carbonate up so the marine organisms can’t use it.) The organisms that are impacted by this problem are facing threats of increased predation and slower growth. A decrease in population of certain keystone species can negatively affect the ecosystem at large.

Off the coast of La Jolla and up and down the west coast, for example, the California mussel (Mytilus californianus) is one of the most common and important species. By comparing museum specimens UC San Diego scientists have seen that mussel shells have weakened over the last 60 years, and they have an idea of exactly how the shells of these organisms are being altered. The data suggest that the mussel’s weakened shell is due to a replacement of the mineral aragonite—a much stronger component—by the mineral calcite, a weaker substance that does not dissolve as easily due to changes in acidity. With increasingly acidic water the stronger mineral aragonite is more scarce, while calcite becomes more prominent and widely used in shell composition by the California mussels. This change in mineral composition has led to weaker shells that could spell disaster for this foundational marine species.

11: Geology Rocks!

12: DDT pollution: A Killer Chemical

History

DDT, the abbreviated form of the chemical Dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane, was first used as an insecticide in the 1940’s. The chemist who discovered the insecticidal properties of the chemical, Paul Hermann Muller, would go on to be awarded a Nobel Prize for his research. DDT was quickly promoted by the United State’s government for its use in agriculture and medicine; in fact, the use of DDT directly correlated to a drastic decline in cases of malaria, typhus, and yellow fever.

As DDT became more widely used, scientists began raising flags about the effects of DDT on the ecology of our natural land. While DDT was effective in killing insects, it impacted other wildlife as well. Rachel Carson, a marine biologist and popular author, wrote a book entitled Silent Spring (named for the impact of pesticides like DDT on bird populations) criticizing the long-term effects of pesticide usage on the environment. The book proved to be monumental in the foundation of the environmental movement within the United States. Following this outcry, the US banned DDT and similar pesticides for agricultural use in 1972.

Peregrine Falcon Recovery

While the use of DDT led to a great decline in animal species, the progress in recovering at-risk species following the banning of DDT inspires ecological work to this day. The peregrine falcon (Falco peregrinus), a resident of the Scripps Coastal Reserve, had been facing an enormous decline in population due to DDT use. Along with the bald eagle, the peregrine falcon had been laying thinner egg shells than usual leading to a decrease in successful hatchings. Research would later suggest that the consumption of DDT (through fish, insects, or other animals) had led these birds to create weakened shells. At their worst, the peregrine falcon was practically extinct in the United States. Yet following the ban of DDT, the falcon population was allowed to recover and they were officially removed from the United States Endangered Species list in 1999. You can often see a glorious pair of peregrine falcons soaring just off of the cliffs of the reserve.

13: Military History

14: The Audrey Geisel University House: Artful Architecture

History

The Audrey Geisel University House is the residence of the University of California San Diego’s Chancellor. The home was originally designed for residents William and Ruth Black and was the first home built within the La Jolla Farms area. The architect was William Lumpkins of Santa Fe, New Mexico and the house is built in the Pueblo Revival style. In 1967 the house was sold to the UC Regents where it would become the home for the standing UC San Diego chancellor. In 2013, a $10 million renovation was funded in part by Audrey Geisel (widow of Theodor Seuss Geisel or Dr. Suess), and the house was renamed in her honor. The site is now listed in the National Register of Historic Places, due both to the historically significant architecture of the home and to the cultural importance of the land to the Kumeyaay people, who have lived in the area since time immemorial and consider this site to be sacred.

15: Anthropogenic Impacts

Living Sustainably

Voting for leaders that are willing to do something about climate change and other environmental issues is the single most important thing you can do to protect the natural systems on which all life depends. After that, living a sustainable lifestyle is an additional way you can help. Living sustainably means you are using the Earth’s natural resources in a way that benefits you while not harming the needs of those in the future. In your typical day to day routine, living sustainably could include limiting your meat intake, avoiding single-use plastics, or carpooling to work. As a community, sustainable development must include replacing CO2-producing fossil fuels with renewable energy sources— solar, wind, or geothermal.

Water Runoff

Water runoff from your home or garden can change nearby ecosystems. At the Scripps Coastal Reserve, for example, the presence of water runoff has allowed for the dominance of the Argentine Ant (Linepithema humile), an invasive species that tends to outcompete all native ant species. In limiting runoff, consider the following solutions:

- Shorten the amount of time that your sprinkler systems run.

- Plant native plants, which require less water, in your garden.

- Use garden soil with a fast absorption rate to limit the time your sprinklers are on.

- Check the range of your sprinkler system, and ensure that you aren’t watering any non-plant areas.

- Check your sprinklers frequently and repair any leaks or breaks

Noise Pollution

Noise pollution occurs when sounds from homes or businesses are loud enough to impact nearby environments. Excessive noise can have a huge impact on animals that rely on sound to survive. Birds who can’t hear their mates call, squirrels who can’t hear a nearby predator, or even bats who can’t effectively hunt through echolocation are examples of the impacts noise pollution can have on an ecosystem. In limiting noise pollution, consider the following solutions:

- Limit your use of amplified noise, particularly at night or early morning.

- Turn off your heavy appliances when not in use.

- Keep up with the regular maintenance of your vehicles or other heavy machinery.

- Consider sound-proofing your walls.

Light Pollution

Light pollution refers to any artificial light entering the environment and altering the amount of light available. You have likely noticed light pollution near cities when you look up to the sky and are unable to see the stars, this is due to the excess of artificial light being created and spread into the sky. Light pollution can negatively impact the lives of animals that are attracted to light, such as sea turtles, moths, or frogs. In limiting light pollution, consider the following solutions:

- Turn off all lights (whether indoor or outdoor) when not in use.

- Use motion sensor systems on porch lights as opposed to leaving them on all night.

16: The Kumeyaay People

17: Torrey Pine Trees: It’s Treemendous

Distribution

The native population of Torrey Pine trees is known to inhabit two distinct locations: alongside the coast of San Diego, and the island of Santa Rosa off the coast of Santa Barbara.

Being near the ocean seems to be an important requirement in their distribution due to the unique adaptations they have developed to live in these environments.

Two of a kind

Torrey Pine trees are categorized into two separate subspecies dependent on the location of the tree:

variant torreyana, found in San Diego (right)

variant insularis, found on Santa Rosa Island (left)

Each subspecies also has characteristic phenotypic (physical) differences. For example, the variant insularis is known to have branches that are much more crowded together and drops larger/darker seeds than its torreyana variant.

Bark Beetle Infestation

An infestation of Bark Beetles begins with the burrowing of a tree by an individual, or more commonly a collective of individuals. When the Torrey Pine detects an injury to its exterior it begins to create and allocate resin, a viscous sticky glue, to the area.

The resin itself is usually enough to deter would-be homeowners looking to renovate a Torrey Pine; however when the amount is nonexistent or too little the beetles manage to enter the tree and lay their eggs.

Successful beetles emit pheromones to signal their cohorts to join in on the fun, and eventually destroy the tree from the inside-out.

-

Small but mighty

An individual beetle has little impact on the hardy Torrey Pine, however an infestation of beetles can lead to absolute devastation of the structure of a tree.

-

The power of water

The Torrey Pine uses sap to defend against incoming beetles, but ensuring water is plentiful is critical in allowing for the creation of enough sap to deter pests.

-

Climate change

A increase in drought brought forth by climate change has decimated the ability for many Torrey Pines to create sap and thus defend themselves.

-

How can you help?

Be mindful of your impacts to the environment and volunteer to help educate those that may not be aware of our changing climate!

Conservation

Alongside the structural damage bark beetles create within a Torrey Pine, they are also known to increase the rate of fungal disease.

Therefore the majority of conservation efforts have been focused on preventing the beetles from reaching the tree, primarily through trapping.

Typical bark beetle traps are funnel-shaped (see image on right) and contain lab-produced chemicals meant to mimic the pheromones that a beetle would emit following successful establishment into a tree.

The beetles, attracted to the pheromones, then fly into the funnel and fall down into a larger container where they are incapable of flying out.

The Kumeyaay people

Connections to the land

The Kumeyaay people were the original inhabitants of the land on which the Torrey Pines grow.

The native Kumeyaay people would care for groves of Torrey Pines, of which they would burn regularly and replant the seeds of. The caring for these trees by the Kumeyaay people is believed to be possibly the earliest record of deliberate planting of conifer trees anywhere in the New World.

At the reserve

Especially observant guests to the reserve may notice a few of our very own Torrey Pine trees. The lack of abundance in these trees leads us to believe that the trees located on the reserve were almost certainly planted at some point.

It is uncertain however whether a grove of the Torrey Pine trees called the mesa their home before their newfound history of disturbance.

Want to learn more?

18: Climate Change at a Glance

Climate Change

As you likely know, our planet is experiencing an unprecedented increase in new daily temperature highs. While not always apparent, these changes in temperature can cause enormous effects to the planet’s ecology and our own society. Climate change causes an increase in extreme weather events (such as wildfires, hurricanes, and floods), changes in global rain and snow patterns, unusual melting of sea ice, and ocean acidification.

It is apparent, and has been for decades, that our changing climate is caused by human activity. Increases in our emissions over time, particularly carbon dioxide, methane and nitrous oxide, have led to the trapping of heat in our lower atmosphere through a process known as the greenhouse effect.

At the Scripps Institute of Oceanography, measurements of atmospheric carbon dioxide have been taken since 1958 and displayed in what is known as the Keeling Curve, named after its creator Charles David Keeling. The curve is significant in that it is the first regular & precise measurement that shows a clear increase in CO2 levels within the atmosphere over time.

Carbon Footprint

Your carbon footprint is the amount of carbon emissions your lifestyle is creating. Helping the climate means getting as close to being carbon neutral as possible by reducing or offsetting your personal emissions. Calculating your exact carbon footprint means adding up all the carbon that is produced by your transportation, diet, or other lifestyle choices. Tools exist online to help you calculate this number.

19: Get Involved!

Getting Involved with the Reserve

If you want to learn more about what is happening at the reserves, sign up for our newsletter here.

There are many opportunities to help the reserve.

- Weed Warriors meet every Friday morning to tackle the invasive plant species at the reserve. Summer 8-10 AM; Winter 9-11 AM. Contact nrs@ucsd.edu to sign up.

- Docents educate visitors about the reserve on the 1st Saturday of every month. You can become a docent too! Contact nrs@ucsd.edu to sign up.

- Visit the reserve during our open hours (1st Saturday of every month, 9 a.m. - 11 a.m.). No registration is needed, just bring your curiosity!

- Become a citizen scientist! For example check out iNaturalist, a social network used in mapping and sharing the observation of plant and animal life around the world. By making your own observations you can help document and preserve biodiversity.

Donate to the UCSD Natural Reserve System. We are a small organization within the larger university, even a small donation will go far in protecting biodiversity or educating students about conservation.

What can you do from home?

Helping out from home is also easy. Consider upgrading your home garden with native plant species. By doing so, you will be helping preserve biodiversity and giving much appreciated support to native pollinators and other animals. In San Diego, native plants also require less water so you’ll see an added benefit to your water bill! Visit the San Diego chapter of the California Native Plant Society for inspiration.

Student Opportunities

If you are a UCSD student and would like to get involved with the reserve, consider enrolling in Conservation Solutions (ENVR 105) when offered. In the class you will learn all about the reserve - everything from what ants live here to how places like this are critical for our climate resilience. You will then become a Conservation Docent and share your passion for wild places like this with other students and with the community. Students in Coastal Ecology (ENVR 120) visit the reserve as well as many other coastal locations to observe and collect natural history data. BILD 4 students also visit and have been working to understand the soil microbiology at the reserve.

The Ecology, Behavior & Evolution (EBE) Club is a student-led organization that grants opportunities for fellow students to network with professionals surrounding careers related to the environment. Other opportunities with the club may include hikes, nature walks, or habitat restoration events. Learn more here

Students interested in immersing themselves in field ecology for a quarter should consider applying for the UC California Ecology and Conservation course. Students spend seven weeks visiting multiple UC NRS sites where they learn about the natural and cultural history of each site and collaboratively design, implement, and communicate a research project.

The California Public Interest Research Group (CALPIRG) is a citizen-funded advocacy group that focuses on issues surrounding the environment and public health. Volunteering with CALPIRG Students may involve direct advocacy against special interest groups by means of petitioning or campaigning for change. Learn more here